He Turned a Machine Gun Into a Sniper Rifle — 93 Kills Made the Viet Cong Put a Bounty on His Head_us

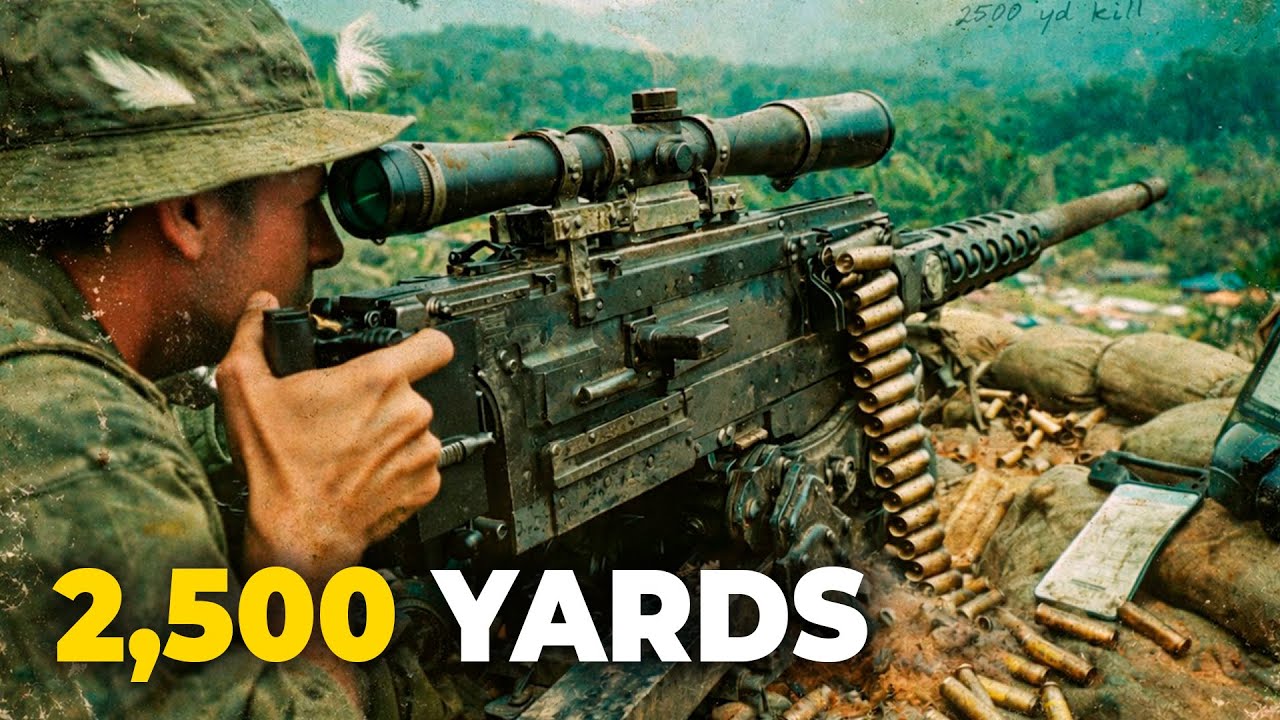

In the summer of 1967, on a mountain position overlooking a valley infested with North Vietnamese Army regulars, a 25-year-old Marine Sergeant did something that would have gotten most men laughed out of the service. He took the top cover off an M2 Browning heavy machine gun, a weapon designed for suppressive fire at enemy formations, and he had Navy Seabees weld a mounting bracket onto it.

Then he attached an 8-power Unertl scope, the same kind of scope he used on his sniper rifle. Except this was not a sniper rifle. This was an 84-pound crew-served weapon that fired belt-fed ammunition at rates up to 850 rounds per minute. The Marines watching him work likely thought he had lost his mind. His commanding officer, Captain Edward James Land, knew better.

Land had watched this Arkansas farm boy shoot for months. He had seen what others refused to believe. The man with the white feather tucked into his bush hat was about to redefine what was possible with a rifle. Any rifle. Even one that was not supposed to be a rifle at all. Carlos Norman Hathcock II was born on May 20, 1942, in Little Rock, Arkansas, to parents whose marriage would not survive his childhood.

When they separated, young Carlos was sent to live with his grandmother Myrtle, in the small town of Wynn, in the flat cotton country of eastern Arkansas. He would spend the next 12 years in her care. It was not an easy life. The depression had left deep scars on rural Arkansas, and food was never guaranteed.

Carlos learned to shoot not because it was a hobby, but because it put meat on the table. His father had brought back a German Mauser from the First World War, a non-functioning relic that young Carlos carried through the woods pretending to hunt imaginary enemies. But his real education came from a battered J.C. Higgins .22 caliber single-shot rifle.

His grandmother gave him the rifle and a handful of cartridges, and the message was clear, if you miss your family goes hungry. He did not miss often. The boy developed an understanding of marksmanship that went beyond technique. He learned patience. He learned to read wind and terrain. He learned that the shot itself was only the final moment of a process that began hours, sometimes days, earlier.

He hunted squirrels and rabbits through the Arkansas timber, moving so slowly that the animals never knew he was there until it was too late. These were not skills anyone taught him. They grew from necessity, from long afternoons alone in the woods, from the pressure of knowing that accuracy meant survival.

Carlos dreamed of becoming a United States Marine from the time he was old enough to understand what Marines were. On May 20, 1959, the day he turned 17, he walked into a recruiting office in Little Rock with his mother’s written permission and enlisted. Boot camp at Marine Corps Recruit Depot San Diego revealed what his grandmother’s woods had already shaped, a natural marksman of extraordinary ability.

He qualified at the expert level, the highest designation, shooting 248 out of a possible 250 on the qualification course. Instructors took notice. Over the next several years, Hathcock’s reputation grew within the small world of Marine Corps competitive shooting. He was assigned to the Marine Corps shooting team and began competing at matches across the country.

In 1962, he transferred to Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point in North Carolina, where he set a record on the A-range that would stand until the course was That same year, on November 10, the Marine Corps birthday, he married Josephine Bryan, a woman who would remain by his side through everything that followed.

The defining moment of his competitive career came on August 26, 1965, at Camp Perry, Ohio. The national matches at Camp Perry were the most prestigious rifle competition in America, drawing the finest marksmen from every branch of the military and civilian shooting organizations. The culminating event was the Wimbledon Cup, a thousand-yard rifle match that tested everything a shooter had learned about long-range precision.

Carlos Hathcock, 23 years old, won it. He was now the long-range rifle champion of the United States. One year later, he deployed to Vietnam as a military policeman. It would not take long for someone to recognize that this particular MP belonged somewhere else entirely. The Marine Corps had a problem in Vietnam, and Captain Edward James Land intended to solve it.

The Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army had snipers, good ones. They operated in the dense jungle around American firebases, picking off Marines with patient, methodical precision. One shot, one kill, then they disappeared into the green. The Marines had no organized response. They had no sniper program, no dedicated training, no doctrine for counter-sniper operations.

Land, who had founded the Corps’ first modern sniper course back in 1961, was given the task of building one from scratch in a combat zone. He had no rifles. He had no instructors. He did not even have an office. What he had was authorization to recruit from anywhere in the Marine Corps, and he had a list of every distinguished marksman in Vietnam.

When he saw that the reigning Wimbledon Cup champion was serving as a military policeman somewhere in country, he made a phone call. Hathcock arrived at Hill 55 in late 1966. The firebase sat 16 kilometers southwest of Da Nang, overlooking the confluence of three rivers, and the approaches to the vital airbase.

The Marines had secured it earlier that year, after extensive mine-clearing operations, and it had become the headquarters for the 1st Marine Division’s scout-sniper operations. Land established his training program in a converted connex box, teaching Marines the fundamentals of long -range shooting, with whatever equipment he could scrounge.

Hathcock was different from the other students immediately. It was not just his shooting ability, though that was exceptional. It was his patience, his stillness, his apparent ability to become part of the itself. Land would later describe it in simple terms. Carlos became part of the environment. He totally integrated himself into the environment.

Other men could shoot, Hathcock could hunt. He began wearing a white feather tucked into the band of his bush hat. It was a deliberate provocation, a calling card, a dare. The feather made him visible, identifiable, a specific target rather than just another American sniper. Some thought it was foolish bravado.

Hathcock saw it differently. He wanted the enemy to know exactly who was killing them. He wanted to be the one they feared above all others. The psychological effect was calculated, and intentional. The North Vietnamese noticed. They began referring to him as Long Trần, White Feather, and then they put a price on his head.

Bounties on American snipers were common in Vietnam. Most were worth between $1,000 and $2 ,000, substantial sums for local fighters. The bounty on the White Feather sniper was $30,000. It was, as far as anyone knew, the highest price ever placed on an individual American soldier in that war. The message was clear.

This man had become a strategic problem. Hathcock’s response was to keep wearing the feather. Other Marines in his area began wearing White Feathers too, spreading the risk, confusing the enemy hunters. It became a point of pride for the unit. If the enemy wanted White Feather, they would have to sort through dozens of potential targets, never knowing which one was the real thing, until it was too late.

His kill count began to climb. In Vietnam confirmed kills required verification by the sniper’s spotter, and a third party, usually an officer. Since snipers often operated deep behind enemy lines without accompanying officers, many kills went unconfirmed. Hathcock estimated that he actually killed between 300 and 400 enemy soldiers during his time in Vietnam.

The official count, the one verified to military standards, would eventually reach 93, but it was not the numbers that made him legendary. It was the missions. Around Hill 55, there operated a female Viet Cong platoon leader, known to the Marines as Apache. She had earned her name through a practice that made even hardened combat veterans sick.

Apache tortured, captured Americans. She did not simply kill them. She made their deaths last, and she made sure their comrades could hear. In November of 1966, Apache captured a Marine private near the firebase perimeter. What followed lasted through the afternoon, and into the next day. The Marines on Hill 55 could hear the screaming.

They could not intervene. When Apache finally released her victim, he staggered toward the wire, his skin partially removed, his eyelids gone, his fingernails torn out. He died at the perimeter, within sight of men who could not save him. Hathcock took it personally. He had arrived in her territory, and she was operating in his.

One of them would have to go for weeks. Hathcock and Land hunted Apache, learning her patrol patterns, trying to predict where she would appear. Then, late one afternoon, Land spotted a group of figures moving up a small rise approximately 700 yards away. One of them matched Apache’s description. She carried a scoped rifle.

When she reached the top and stepped off the trail, Hathcock took the shot. It was, he would later say, one of the best shots he ever made. He put a second round into her for good measure. The North Vietnamese responded by sending their own expert after White Feather. The enemy sniper was known only as the Cobra.

He was sent specifically to kill Carlos Hathcock, and he began his campaign by killing Marines around Hill 55 in a deliberate effort to draw White Feather out. One of his victims was a gunnery sergeant shot outside Hathcock’s own quarters. Hathcock watched him die. He made a vow. He would get the Cobra one way or another.

Hathcock took his spotter, Corporal John Roland Burke, and they went hunting. The jungle around Hill 55 became a chessboard, two master players circling each other through the green maze, each trying to predict the other’s movements, each knowing that the first mistake would be the last. The Cobra was good, very good.

Hathcock would later describe him with something approaching respect. He was very cagey, very smart. He was close to being as good as I was. But no way. Ain’t nobody that good. The encounter that ended it came without warning. Hathcock and Burke were moving through dense vegetation when Hathcock stumbled over a rotted log.

At that exact moment, the Cobra fired. The round struck Burke’s canteen, and for a terrible instant, both men thought he had been hit. They felt the warmth spreading down his leg before realizing it was just water. The hunter and the hunted had traded places. Hathcock knew the Cobra was close, watching, waiting for another opportunity.

He scanned the jungle ahead, looking for any sign of his enemy, and then he saw it. A tiny glint, light reflecting off glass. A scope lens. Hathcock understood instantly what that glint meant. The only way he could see light reflecting off the front of the Cobra’s scope was if the Cobra was looking directly at him.

Both snipers had their crosshairs on each other at the same moment. One of them would fire first. Hathcock fired. The round went straight through the enemy sniper’s scope, through the optical elements, and into his eye. Hathcock’s bullet had traveled the length of the tube without touching the sides. When he examined the body, the scope was hollowed out, the bullet’s path perfectly centered.

It was a shot that should have been impossible. It meant that Hathcock had pulled the trigger in the fraction of a second before the Cobra could do the same. He took the rifle as a trophy. It was stolen from the armory, before he could bring it home. If you want to see how a farm boy from Arkansas redefined what was possible in in countless films and television shows, often dismissed as Hollywood fiction by those who did not know its origin.

But Hathcock had more impossible shots to make. The M2 Browning heavy machine gun had been in American service since 1933. It was designed for sustained suppressive fire, mounted on vehicles and fortifications, crewed by multiple soldiers. No one had seriously considered it a precision weapon. The gun was too heavy, the ammunition too variable, the entire concept absurd on its face.

Hathcock saw something different. The .50 BMG cartridge was ballistically superior to any rifle round in the American inventory. If you could control the weapon, if you could fire it in single-shot mode with a proper aiming system, you could reach out to distances that conventional sniper rifles could not touch.

The problem was building a setup that would actually work. He worked with Navy Seabees, the construction battalions that could build anything from airstrips to bridges under combat conditions. They fabricated a mounting bracket that would accept his unheard of scope. He balanced the weapon on an M3 tripod, stabilized it with sandbags, and spent hours testing different lots of belt-fed ammunition to find the rounds that shot most consistently.

Some Marines thought he was wasting his time. Machine guns were not sniper rifles. Everyone knew that. Hathcock established a position on an elevated observation point, surrounded by enemy activity so intense that patrols could not safely leave the perimeter. He spent three days observing, mapping enemy movements, zeroing his improvised weapon.

The closest range he could reliably hit was 1,000 yards. The farthest was 2,500. On the third day, a Viet Cong soldier appeared at approximately 2,500 yards, pushing a bicycle loaded with weapons and ammunition down a trail. The Ho Chi Minh Trail was an endless supply line, and this was one small part of it. Hathcock watched through his scope as the figure moved across the zeroed position.

He fired. The round struck the bicycle, sending it tumbling. The soldier, who appeared to be quite young, scrambled to his feet. Instead of running, he grabbed one of the rifles from the scattered cargo and began shooting in Hathcock’s direction. The rounds fell far short. Hathcock fired again. The approximately 2,500-yard shot was, at that moment, the longest confirmed sniper kill in recorded history.

It beat a record that it stood for nearly a century since buffalo hunter Billy Dixon killed a Comanche leader at the Second Battle of Adobe Walls in 1874. Hathcock had made the shot with a weapon no one believed could be used for precision shooting, firing standard belt-fed ammunition at a moving target. The record would stand for 35 years until Canadian snipers using purpose-built, .

50-caliber rifles with match-grade ammunition finally surpassed it during the war in Afghanistan in 2002. They had decades of technological advancement. Hathcock had ingenuity and a scope strapped to a machine gun. But perhaps his most remarkable mission came near the end of his first tour, a volunteer assignment so dangerous that command did not explain the details until he agreed to take it.

The target was a North Vietnamese Army general operating from a heavily defended encampment. The only approach was across more than 1 ,500 yards of open terrain, fields and meadows with minimal cover, patrolled constantly by enemy soldiers. There was no conceivable way to get within rifle range without being detected.

Unless you were Carlos Hathcock, you removed the white feather from his hat. This was the only time during his Vietnam service that he would do so. He was inserted by helicopter at a distance from the target area and began what he called worming inch by inch crawling across open ground, moving so slowly that the motion was nearly imperceptible.

For four days and three nights, without food without sleep, Hathcock wormed his way toward the enemy camp. He moved on his side to keep his trail as narrow as possible. He covered himself with grass and vegetation until he was indistinguishable from the meadow itself. He would later describe coming so close to patrolling enemy soldiers that he could have tripped them.

They walked past without ever seeing him. At one point a bamboo viper slithered toward his position. The snake was highly venomous. Moving would reveal his location to nearby patrols. Hathcock remained absolutely still, controlling his breathing, controlling his heartbeat, willing himself into invisibility until the snake moved on.

He reached a firing position approximately 700 yards from the enemy encampment, positioned between two twin .51 caliber machine gun emplacements. The gunners never knew he was there. Morning came. The general stepped out onto a porch and yawned. An aide moved in front of him briefly, blocking the shot. Hathcock waited.

The aide stepped away, one shot, through the chest. The general collapsed. Everyone in the camp ran toward the treeline, the logical place for a sniper to hide. Hathcock was in the grass behind them. He crawled to a drainage ditch and began the long journey back. It took three more days. Enemy soldiers searched for him continuously.

They never found him. His commanding officer summarized the mission simply. Carlos became part of the environment. The mission is sometimes questioned by historians who note that no North Vietnamese general is documented to have died of gunshot wounds during Hathcock’s period of service. The discrepancy may reflect the difficulties of wartime record-keeping, deliberate enemy concealment of leadership casualties, or questions about the target’s actual rank.

What is not disputed is that Hathcock successfully infiltrated a heavily defended position using methods that seemed physically impossible and without being detected. Hathcock returned to the United States in 1967 with 86 confirmed kills. He was exhausted, burned out by the cumulative stress of operating under a $30,000 bounty.

He was discharged and reunited with his wife and young son in Virginia. He re-enlisted one week later. In 1969, Hathcock returned to Vietnam for a second tour, this time commanding a platoon of snipers. He was back where he belonged, teaching the skills he had developed, leading men who looked up to him as a legend made flesh.

It would not last. On September 16, 1969, Hathcock was riding on an LVTP-5 amphibious assault vehicle along Highway 1, north of landing zone Baldy. The LVTP-5 was an armored personnel carrier, designed to deliver Marines from ship to shore and provide protected transport in combat zones. It was not designed to survive a 500 -pound anti-tank mine.

The explosion was catastrophic. The vehicle was immediately engulfed in flames. Hathcock was sprayed with burning gasoline. He was knocked unconscious, then awoke in the fire. What happened next defined Carlos Hathcock as much as any shot he ever made. He went back into the burning vehicle. Seven Marines were still inside.

One by one he pulled them out, dragging them to safety while his own skin burned. He did not stop until every man was clear. Only then did someone pull him away and place him in water. He had not realized how badly he was injured. Burns covered more than 40 percent of his body. Some were third degree, destroying the full thickness of his skin.

His face, his arms, his legs, all were damaged. He was evacuated by helicopter to USS Repose, a hospital ship, then to a naval hospital in Tokyo, and finally to the burn center at Brook Army Medical Center in San Antonio, Texas. The recovery took months. When he was finally discharged, he walked with a limp and had limited use of his right arm.

His career as a combat sniper was over. He was 27 years old. Hathcock was recommended for the Medal of Honor for his actions at the burning vehicle. He refused. He did not believe that saving fellow Marines was medal-worthy. It was simply what you did. Nearly 30 years later, in 1996, he finally accepted a Silver Star for the same action.

By then he was in a wheelchair, barely able to stand, his son helping to hold him upright during the ceremony. After his recuperation, Hathcock was assigned to help establish the Marine Corps Scout Sniper School at Quantico, Virginia. It was work he was born to do. Everything he had learned in the Arkansas woods, everything he had refined in the jungles of Vietnam, now became doctrine.

He taught Marines the fundamentals of long-range shooting, but more importantly, he taught them how to think like hunters, how to become part of the environment, how to wait. He called it getting into the bubble, a state of complete concentration where nothing existed except the target and the shot. It was not something that could be taught through lectures.

It had to be demonstrated, experienced, absorbed through practice until it became instinct. The injuries from the mine never fully healed. Hathcock lived with constant pain. In 1975, his health began to deteriorate in new ways. He was diagnosed with Multiple Sclerosis, a disease that attacks the nervous system, progressively destroying the ability to control muscles and movement.

Whether the disease was connected to Agent Orange exposure during his extensive jungle operations remains unknown. No definitive link has been established, though the question haunts many Vietnam veterans. Hathcock stayed in the Corps, teaching despite the pain, despite the progressive weakness. His body was failing, but his knowledge was irreplaceable.

Students who passed through his instruction went on to serve in every conflict that followed, carrying his methods forward. In 1979, while teaching at the rifle range at Quantico, Hathcock collapsed. He woke up in an emergency room, losing feeling in both arms, unable to move his left foot. The Marine Corps had no choice but to medically discharge him.

He was 55 days short of 20 years of service. 20 years would have qualified him for regular retirement pay. Instead he received a full disability classification, which actually provided greater benefits, but the distinction mattered to Hathcock. He felt as if the Corps had kicked him out. He fell into a deep depression.

His wife Jo nearly left him. The man who had crawled through open fields under enemy fire, who had faced the Cobra in the jungle, who had saved seven men from a burning vehicle, could not face civilian life. What saved him was unexpected. He took up shark fishing. The patience required, the long hours waiting for a strike, the sudden explosive action when a fish hit the line, connected to something deep in his nature.

The hunt was still there, transformed into something that did not require killing men. Slowly he began to recover. He also returned to Quantico, not as an instructor but as a welcome visitor. Students and staff received him as a living legend. He would sit with young snipers, answering questions, sharing stories, passing along wisdom that could not be found in any manual.

He continued providing training to police departments and select military units, including the Navy’s elite SEAL Team 6. In 1986, author Charles Henderson published Marine Sniper. 93 confirmed kills, a biography that brought Hathcock’s story to a wider audience. The book became a classic, selling over half a million copies and introducing generations of readers to the white feather legend.

Hathcock had never sought fame, but he recognized that his story could inspire others. He cooperated with Henderson and with subsequent biographers, giving interviews that preserved his experiences in his own words. The honors accumulated. The Gunnery Sergeant Carlos Hathcock Award was established to recognize Marines who contributed to the improvement of marksmanship training.

A sniper range at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, was named in his honor. The Rifle and Pistol Complex at Marine Corps Air Station Miramar was officially designated the Carlos Hathcock Range Complex. Springfield Armory produced a variant of their M -21 rifle called the M-25 White Feather, bearing his signature and his famous symbol.

At his retirement ceremony years after his medical discharge, Hathcock was given a plaque that captured what the Corps thought of him. A bronze Marine campaign cover was mounted above a brass plate that read, There have been many Marines. There have been many marksmen, but there has only been one sniper. Gunnery Sergeant Carlos N.

Hathcock. One shot, one kill. Multiple sclerosis is a cruel disease. It takes everything slowly, methodically without mercy. The man who had once crawled 1,500 yards across open ground could no longer walk. The hands that had made impossible shots could no longer hold steady. Carlos Hathcock watched his body betray him one function at a time.

On February 22, 1999, in Virginia Beach, Virginia, Carlos Norman Hathcock II died from complications of multiple sclerosis. He was 56 years old. The enemy that finally defeated him was one he could not hunt, could not out-shoot, could not outlast. He is buried at Woodlawn Memorial Gardens in Norfolk, Virginia.

The Stevens Model 15, a rifle on which he learned to shoot, the unremarkable .22-caliber single shot that started everything, was donated to the National Museum of the Marine Corps at Quantico by his brother Billy Jack. It sits in a display case, looking like exactly what it is, a cheap youth rifle of no particular value.

Most visitors walk past without stopping. They do not know that in the hands of a hungry Arkansas boy, it became the foundation of a legend. Carlos Hathcock’s influence extends far beyond his 93 confirmed kills. The Marine Corps Scout Sniper School he helped establish continues to train America’s finest precision marksmen.

His methods, his patience, his understanding of the hunt, have been passed down through generations of students who never met him but carry his legacy forward. 50-caliber rifle he proved viable as a sniper weapon has become standard equipment in military forces around the world, a direct result of his improvised machine gun experiments in Vietnam.

The shot through the scope, the 2,500 -yard kill, the four-day crawl, these stories have been told so many times that they sometimes seem like fiction. They are not. They were accomplished by a man who learned to shoot because his family needed meat, who dreamed of becoming a Marine, who discovered that war required skills no one could teach except the land itself.

He never enjoyed the killing. He said so repeatedly, in interviews throughout his later years. You would have to be crazy to enjoy running around the woods, killing people. But if I did not get the enemy, they were going to kill the kids over there. The kids dressed up like Marines. He saw himself not as a killer but as a protector.

Every enemy soldier he stopped was one who would not ambush a patrol, would not plant a mine, would not cut through an American perimeter at night. The white feather became his symbol, his challenge, his defiance. He wore it openly despite the $30,000 bounty because he wanted the enemy to know exactly who was hunting them.

When other Marines took up the feather in solidarity, it became something larger than one man. It became a statement about American resolve, about the willingness to stand openly in the face of threat. His wife Josephine outlived him by 17 years, passing away in 2016. His son Carlos Norman Hathcock III followed his father into the Marine Corps and retired as a gunnery sergeant, the same rank his father held.

The tradition continues. We are rescuing forgotten stories from dusty archives every single day. Stories about marksmen who prove themselves with skill and patience. Real people. Real heroism. Drop a comment right now and tell us where you are watching from. Are you watching from the United States? United Kingdom? Canada? Australia? Our community stretches across the entire world.

You are not just a viewer. You are part of keeping these memories alive. Tell us your location. Tell us if someone in your family served. Just let us know you are here. Thank you for watching and thank you for making sure Carlos Hathcock does not disappear into silence. These men deserve to be remembered, and you are helping make that happen.