EXTREMELY SENSITIVE CONTENT – 18+ ONLY:

This article discusses sensitive historical events related to capital punishment in the United States and the legal process surrounding an execution. The content is presented strictly for educational and historical purposes, to encourage informed reflection on civil liberties, due process, and how fear and ideology can shape justice. It does not endorse, promote, or glorify violence, execution, or extremism. No graphic detail is intended.

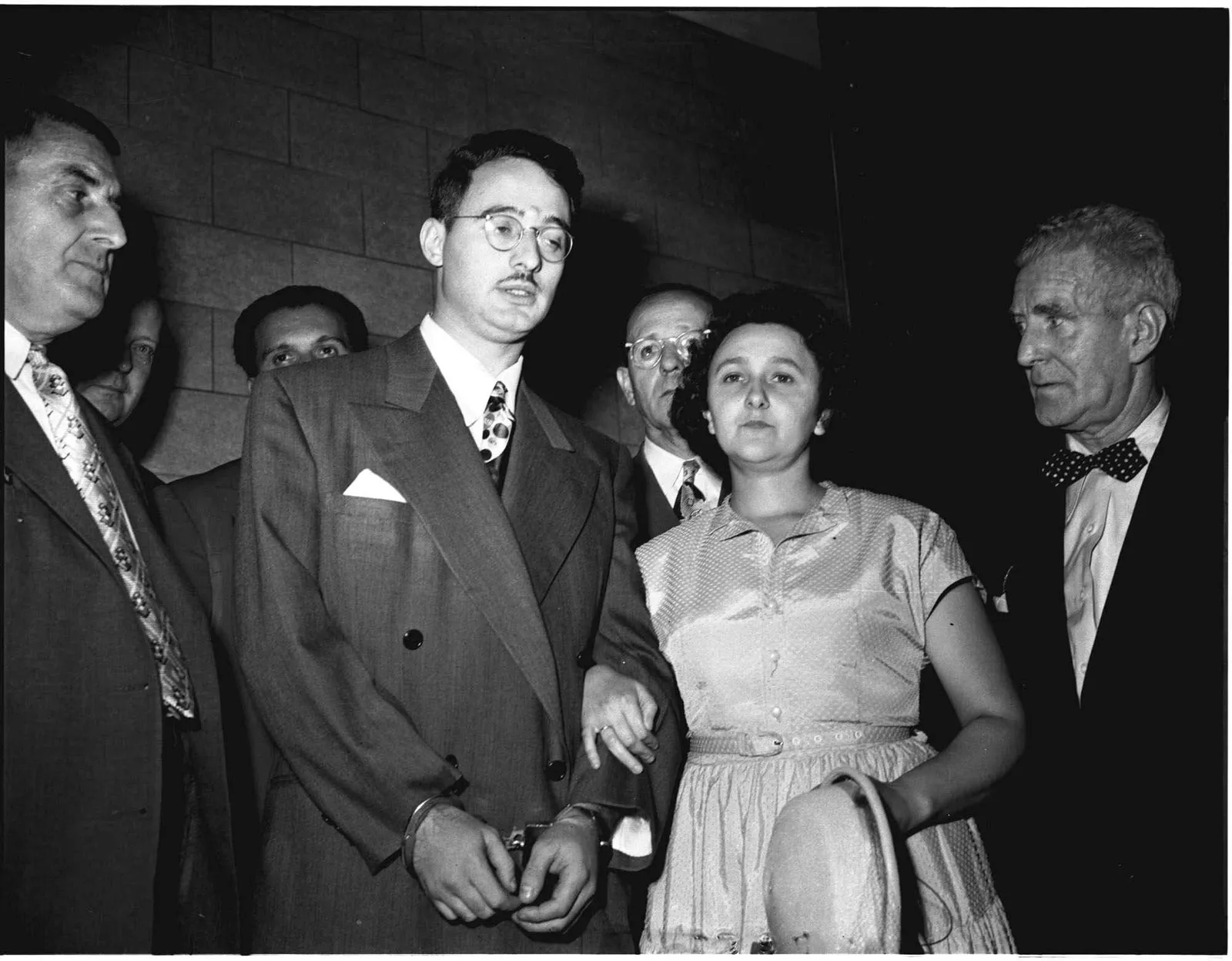

Julius Rosenberg (May 12, 1918) and Ethel Rosenberg (September 28, 1915) were an American couple convicted in 1951 of conspiracy to commit espionage during the early Cold War, accused of passing information connected to U.S. military and atomic research to the Soviet Union. Arrested in 1950 amid intense anti-communist tension in the United States, they were tried in federal court, found guilty under the Espionage Act framework used at the time, and sentenced to death. Their case became internationally controversial, drawing protests and petitions that argued the evidence was insufficient, that the punishment was disproportionate, and that the trial climate reflected political hysteria and prejudice. The Rosenbergs were executed on June 19, 1953, at Sing Sing Prison in New York—an outcome that remains one of the most debated episodes in American legal history. Examining the events dispassionately highlights the era’s anxieties, the human consequences of politicized prosecutions, and the enduring importance of strict procedural safeguards in capital cases.

Their last 24 hours unfolded in a rapidly changing legal and emotional landscape. In the days leading up to June 19, defense attorneys pursued emergency appeals focused on legal interpretations of whether the death penalty provisions being applied were appropriate under the circumstances. On June 17, Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas granted a temporary stay, prompting brief hope that the executions might be postponed while arguments were reviewed. During that window, Julius and Ethel wrote a final letter to their sons, Michael and Robert, expressing love, urging resilience, and attempting to give meaning to a moment they believed was shaped by forces larger than themselves. The language of that letter—calm, deliberate, and protective—has endured because it captures the private voice of parents trying to soften a public catastrophe for their children.

That hope proved short-lived. On June 19, the Supreme Court reversed course in emergency proceedings, clearing the way for the sentence to be carried out that evening. Outside the prison, demonstrations continued as appeals for clemency reached New York’s governor. Prominent individuals around the world added their voices, but clemency was denied. Inside the prison, the Rosenbergs were kept under standard death-row protocol, visited by clergy, and made final preparations separately. Over the decades, popular retellings have embellished the day with dramatic scenes of a last kiss immediately before the execution; however, those claims are not reliably supported by primary documentation from the final hours, and images sometimes circulated with that caption are typically from earlier moments, not the last day itself.

The executions proceeded on the evening of June 19, 1953. Contemporary accounts from official records and reporters describe Julius being taken first, followed by Ethel minutes later. Their deaths, the immediate aftermath, and the fact that their two sons were left orphaned intensified the public argument that had surrounded the case from the beginning. For supporters of the verdict, the outcome represented a severe response to national-security betrayal during a dangerous geopolitical period. For critics, it became a warning about how fear, propaganda, and moral panic can erode legal restraint—especially when the state holds the power to impose irreversible punishment.

Seen through a historical lens, the Rosenberg case is less a single story than a mirror held up to its time: a society gripped by ideological conflict, institutions under pressure to appear uncompromising, and ordinary human beings caught in a machinery that rarely pauses for nuance. Whether one views the convictions as justified or unjust, the final day of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg underscores why due process, reliable evidence, and protections for civil liberties matter most when the stakes are life and death—and why a democracy must be most careful precisely when it is most afraid.